http://www.parenting.com/article/Baby/Daycare--Education/The-Early-Literacy-Crisis#

The Early Literacy Crisis: A Mom Congress Special Report

Too few books and too little time are adding up to a disaster for some of the nation's youngest learners.

By Lisa Moran, Parenting

The Vanda Early Learning Center in Lubbock, TX, sits between two cotton fields, with a bright-blue sign out front and a globe painted on the sidewalk. It's a cheery spot for the children who come here, nearly all of whom qualify for the federal free-lunch program. With its state-endorsed kindergarten-readiness program, it also represents a critical opportunity for them to avoid ending up like the 22 percent of adults over age 25 in Lubbock who don't have a high school diploma.

Zadrian Rodriguez was at high risk of becoming one of those statistics because his mother, Amelia, was struggling to raise three young kids on her own. "I was working long hours and I didn't have time to sit down with them or read to them," she says. Like more than half of the families whose children attend Vanda, Rodriguez also didn't have any books at home. And those are huge problems.

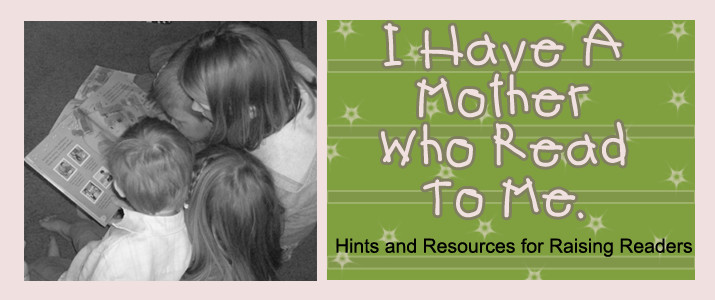

Research has repeatedly shown that access to books and one-on-one reading time is an important predictor of future literacy skills.Reading to your baby from infancy on exposes her to the alphabet, to the sounds that words make, and to the idea that print letters translate into spoken words. Talking to your child about a story boosts understanding and vocabulary. In contrast, not having this language and literacy exposure can quickly set kids like Zadrian and his siblings up for failure. Many children who enter kindergarten without pre-reading skills in place never catch up, according to "America's Early Childhood Literacy Gap," a 2009 report from Jumpstart, a national early education organization dedicated to advancing school readiness in low-income communities. "By second grade, we can predict with reasonable accuracy who will go on to higher education and who will not, based on their literacy skills," says Jumpstart board member Laura Berk, Ph.D., professor of psychology at Illinois State University.

A parade of experts echo this sentiment: If a child isn't caught up by third grade, "it requires intense intervention to close this gap," says Janice Im, senior program manager at Zero to Three, a nonprofit that promotes healthy development in babies and toddlers.

"We have faith in education and how it works, but the truth is that these kids don't catch up no matter how good their schools are," agrees Adam Ray of the Pearson Foundation, the nonprofit arm of the media giant, which helps fund Jumpstart's work.

Having reading difficulties also increases the odds that a child will drop out of school and have a criminal record. States like California and Indiana have even factored in the number of third-graders who are not reading at grade level when planning future jail construction. But the news isn't all bad: There's a growing understanding of the urgent need to help young kids develop literacy skills, and organizations like Jumpstart are stepping in to help.

READING BETWEEN THE LINES

In 2002, government agencies convened the National Early Literacy Panel (NELP) to understand what helps children from birth to age 5 learn to read when they get to school. Their report, "Developing Early Literacy," released last year, analyzed 500 studies and used the results to define a specific set of skills that predict later literacy achievement for children in kindergarten, explains NELP panel chair Timothy Shanahan, Ph.D., director of the Center for Literacy at the University of Illinois at Chicago. "We're not talking about sitting kids down with workbooks," notes Shanahan, "but you still need a plan to teach a child literacy skills through play."

Children also need access to books, and far too many don't have that. While a child growing up in a middle-class neighborhood will own an average of 13 books at any given time, low-income communities average about one book for every 300 children, according to University of Michigan professor Susan Neuman, Ed.D., author of Changing the Odds for Children at Risk. Even all libraries aren't created equal: School libraries in low-income areas average half the number of children's books as those in middle-income neighborhoods, and public libraries in these communities often have more restrictive hours of operation. "Physical and psychological proximity to books and reading materials is critical. A child can't pick up a book that isn't there," says Neuman.

A language-rich environment, in which parents talk to their children, ask questions, and involve them in an ongoing dialogue, is also essential to emerging literacy. One often-cited study estimates that by the time kids enter school, there can be a difference of 30 million words between the vocabularies of children growing up in well-off households versus the vocabularies of children in poorer ones. These children "often haven't been exposed in their interactions with their parents to the alphabet, vocabulary, and language skills," according to Susan Landry, Ph.D., founder and director of The Children's Learning Institute at the University of Texas Health Science Center, in Houston.

HELP IS ON THE WAY

Enter groups like Jumpstart, whose corps of volunteers, a nationwide team of trained community residents and college students, provides intervention in 260 preschools and childcare facilities. Corps members spend six to eight hours each week -- for an entire school year -- reading with kids and doing activities that develop social, language, and literacy skills. The results so far have been impressive: A 2008 review of Jumpstart's program run out of Illinois State University found that the children who received literacy intervention showed fall-to-spring gains in achievement -- on three different tests -- that were two to three times greater than children who did not participate in the program. Zadrian Rodriguez, now 6, benefited from the Jumpstart corps while attending Vanda, and his sister, Nazlyn, 5, is part of the program as well.

Washington seems to be on board, too: Last year's stimulus bill allocated $5 billion for early learning programs like Head Start, a federal program that provides comprehensive early-childhood development services to low-income children. It also included $5 billion in challenge grants to encourage innovative programs that work toward closing "the achievement gap."

The next step: States also need to make early education more accessible. Research has shown that public pre-kindergarten programs increase high school graduation rates, improve academic outcomes, and reduce the number of children who require special-education services, says Marci Young, the director of Pre-K Now, a group working to make quality pre-kindergarten available for all 3- and 4-year-olds. Currently, only 24 percent of 4-year-olds and 4 percent of 3-year-olds in the U.S. are in a state-funded program, according to Pre-K Now.

Public awareness and support for programs that encourage reading is essential as well. A poll by the Pearson Foundation and Jumpstart found that while 95 percent of Americans consider early childhood literacy an important issue, they were not aware that reading to a child between the ages of 3 and 5 is critical for future achievement.

Zadrian Rodriguez is proof of that. Now a first-grader at Hodges Elementary in Lubbock, the little boy loves reading the books he brings home from the school library. His sister, Nazlyn, just got her first book, Eric Carle's The Very Hungry Caterpillar, from her participation in Jumpstart's program. Wednesdays are Zadrian's favorite day at school because that's when they have spelling tests. "He loves when he gets a hundred," says Amelia Rodriguez. "We put it on the refrigerator and we all give high fives." With enough noise, maybe state and federal elected officials can also give a big high five to early literacy education for all.

No comments:

Post a Comment